Pure Cotton and Mixed Fiber: A Flourishing Era

The terms “Pure Cotton” and “Mixed Fiber” (Japanese: ファイバー, meaning “fiber”) originated as the insider terminology during the Japanese colonial period to describe the different art form of Shingeki (meaning “new drama”) in terms of stylistic orientation. In this lexicon, “Pure Cotton” referred to troupes that adhered strictly to the imported Japanese Shingeki conventions: using written scripts, maintaining rehearsal systems, and thus considered orthodox. In contrast, “Mixed Fiber” described certain Taiwanese theatre troupes that, under wartime policy of Japanization, were compelled to perform Shingeki rather than their original plays. These troupes incorporated elements of Chinese opera techniques and sometimes self-proclaimed as “Taiwanese New Theatre” or “Taiwanese Opera.” Although the Shingeki troupes styled themselves as “Pure Cotton,” implying the others were unorthodox, Japanese Shingeki itself was in fact a hybrid genre that drew from Western modern drama. The Japanese loanword ファイバー, literally and phonetically meaning “fiber,” carried no implication of impurity; it denoted artificial or modified textiles, reflecting the surge of synthetic fibers during the Second World War. The Chinese translation Huaiba (literally “bad stick” or “bad handle”) could imply a pejorative tone, yet the origin of ファイバー was neutral without insinuation.

Hence, placing the concept of “Pure Cotton” and “Mixed Fiber” within the context of Taiwanese theatre history becomes conceptually rich and dialectical. While “Pure Cotton” implied legitimacy rooted in the purity of bloodline, its true nature as a modern hybrid art form was overlooked. Moreover, though proclaimed as pure and orthodox, the Shingeki troupes drew upon traditional operatic materials or adapted from films and novels. The terms “Pure Cotton” and “Mixed Fiber” marked a brief phase of self-identification during the nascent stage of Taiwanese modern theatre, while simultaneously signaling the intersection of old and new theatrical forms. Viewed from another perspective, “Pure Cotton” could signify self-definition, whereas “Mixed Fiber” might represent self-driven innovation. Both orienting forward, both asserting their own versions of “orthodoxy.”

Since the arrival of Han immigrants, the performance practices of Taiwanese theatre have been influenced by intonation and dialectal variations, resulting in a diverse theatrical landscape imbued with immigrant influences. Luantan opera was once the most prevalent form during the Qing dynasty; however, its exact origin is difficult to trace, and it is now recognized as one of Taiwan’s traditional theatre forms. Baizi and Siping operas, derived respectively from southern and northern nanguan and beiguan vocal traditions, once held their own regional influence in Taiwan, but their exact sources remain ambiguous. The idea of purity and orthodoxy is elusive, while hybrid forms proliferate, sometimes becoming the local “Pure Cotton.” Glove puppetry serves as the best example: originating as a genre that plays by traditional scripts, it evolved into swordplay puppetry, Golden Light puppetry, and even televised glove puppetry shows, which are all unique to Taiwan. Hakka opera started out as simple Tea-picking opera, but after integrating elements of beiguan Luantan and Taiwanese opera, it culminated in the form of grand Hakka opera, incorporating various tunes and vocal styles. Taiwanese opera similarly builds upon beiguan and nanguan traditions, as well as Peking and Fuzhou operas, evolving into Taiwan’s major form of vernacular theatre. Its maturation parallels the development of Peking opera, which rose to prominence after synthesizing elements from Han, Hui, and Kun traditions. The dynamics of borrowing, mutation, fusion, and integration in Taiwanese traditional theatre reflect a multicultural ethos. In addition, modernization since the early twentieth century brought extensive Japanese and Western cultural influences. The dynamic interaction between traditional and modern theatre, nourished by a growing commercial market, further enabled the flourishing integration of dance, film, and Western music, which reached their peak postwar. By the 21st century, modern stage conventions have transformed the classic “one table, two chairs” stage setup, yielding new texts and stage forms, as well as performance techniques and technical execution. It is ultimately impossible to determine which is “Pure Cotton” and which is “Mixed Fiber,” as all are subject to human-directed adaptation, shaped by time, place, and people.

The curatorial theme revisits these historical complexities, acknowledging the internal diversity of Taiwanese theatre. It simultaneously draws on Japanese colonial period terminology and embraces the possibilities of cross-discipline, debordering, and hybrid theatrical landscape. Purity signals self-anchoring in technique and stage form, discerning the choices made within the continuity of changes; hybridity, on the other hand, responds to Taiwan’s history of immigration and its colonial modernity, reflecting theatre’s self-renewal and evolving artistic language. Together, both move forward and backward, intertwined. “Pure Cotton” and “Mixed Fiber” are not a set of newly invented binary but a recognition of ongoing dynamism—what was once hybrid might later become orthodox, and today’s hybrids may tomorrow be recognized as “pure.” Within this framework, the “Chef’s Special: Four in Love” presents four productions that lie between purity and hybridity: Gang-a Tsui Theater’s “Zheng Yuanhe and Li Yaxian” preserves the essence of Quanzhou Liyuan opera; Qing Mei Yuan Luantan Opera Troupe stages “Leaving the Capital”, a once-popular beguan Fulu opera; Lee Ching-fang Taiwanese Opera Troupe revives the signature work of masters Hung Ming-hsueh and Hung Ming-hsiu, “Meng Jiangnu’s Bitter Weeping”, and Minkuan Taiwanese Opera Troupe integrates Western music into one of the four canonical Taiwanese opera plays, “The Butterfly Lovers”.

The program”Let’s puppet party” presents another rich medley of glove puppet performances. Hung Chi-wen, lead puppeteer of Chuan Hsiyuan Glove Puppetry Troupe, performs “Friendship”, a traditional play learned from Master Hsu Wang. Se-den Society Puppet Troupe, Huang Ming-Long also under Master Hsu Wang’s tutelage, stages a newly created swordplay drama, “The Golden Flute Wanderer: Origins”. Ngo.lng-Tshiong lead puppeteer of Honĝ Oán Jiân Classical Puppet Troup, apprenticed under Masters Lee Tien-lu and Chen Hsi-huang , performs the Northern-style Waijiang drama “Hong Ni Gate”. Finally, Ling hung-hsien of Guang Xing ge Puppet Troupe, a renowned Golden Light Puppetry troupe from Southern Taiwan, presents “The Stealthy Valley PART:ZERO”, a reconstructed work rooted in traditional forms.

Kiong lo̍k-siā (拱樂社) in Mailiao, Yunlin, a representative troupe of the 1950s, embodied both “Pure Cotton” and “Mixed Fiber” characteristics: adopting playwriting/directing systems, hiring professional scriptwriters, and integrating Western music, dance, serialized plays, and recorded performances. Its first commissioned production, “Kim-gîn Tengu”, clearly bore influences from Japanese Shingeki and Fuzhou Peking opera. Authorized by the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute, the National Taiwan College of Performing Arts restages “Kim-gîn Tengu” as the flagship production, not only paying tribute to the golden era of indoor Taiwanese opera but also resurrecting Kiong lo̍k-siā (拱樂社)’s historical splendor and the once-vibrant popular market for serialized plays.

This year, the program also inaugurates the “Director Showcase,” conceived in the same spirit to reflect on how traditional theatre has been shaped by modern theatrical systems. From storytelling and scene direction to actor embodiment and professional specialization, the emergence of the director’s role marks a crucial transformation in the performing arts. Bridging the aesthetics of traditional and modern stage direction, Chen Sheng-guo, chief director of the Ming Hwa Yuan Arts & Cultural Group, stands as a living witness to this evolution—an artist who inherits the lineage of the traditional storyteller while redefining the role of the modern director. From “Father and Son” (1982) which rose to fame in the Local Theatre Competition, to “Drunkenly Losing the Kingdom”, a reconstructed classic by his father Chen Ming-chi, and the newly devised “Kunlun” these three works of distinct styles—presented alongside artist talks—trace Chen’s creative journey while opening up broader discussions on the pedagogy and epistemology of directing in traditional theatre.

This year’s selected works further demonstrate the oscillation between orthodoxy and adaptation. Bare Feet Dance Theatre’s “The Shed” reimagines classic beiguan excerpt “Slaying the Melon Demon” within contemporary frameworks. Jingsheng Hakka Opera Troupe’s “The Flirtatious Lü Dongbin and the Lovely Peony”, drawing inspiration from the legend of the Eight Immortals, revitalizes traditional opera from within by reconstructing character relationships, transforming linguistic textures, and blending diverse musical styles. Selected as the flagship production by the Taiwan Taiwanese Opera Center, SunHope Taiwanese Opera Troupe’s “The Meteor” joins this year’s Festival, transforming an ancient Taiwanese myth into a musical-style Taiwanese opera that mirrors the inner struggles and fractured identity of Taiwanese soldiers under Japanese rule. From Korea, “THE TWO EYES”, a co-production by MUTO and IPKOASON, curated by the Asia Culture Center (ACC), integrates the traditional pansori narrative form with contemporary multimedia, presenting a dialogue between oral storytelling and modern visual-sound technology. In addition, National Chinese Orchestra Taiwan with “Spring Scream”, GuoGuang Opera Company with “Heaven and Earth: Li Yu, the Poet Emperor”, and Taiwan Bangzi Opera Company with “Whispers Behind the Window Shade” collectively embody the enduring vitality of innovation and transmission within traditional theatre.

Aligned with the curatorial theme “Pure Cotton and Mixed Fiber,” this year’s program features the exhibition,"Sound Journeys from Traditional Indoor to Contemporary Theatres in Taiwan" at the Taiwan Music Institute. It showcases archival audio-visual materials from both public and private collections, tracing the diverse vocal landscapes of Taiwanese theatre from its early days to the present. These once-blooming voices now converge in vibrant, hybridized patterns, embodying the living spirit of the Pure Cotton and Mixed Fiber ethos.

Hopefully, amid the flourishing spectacle of the stage, audiences will once again experience the full breadth of Taiwanese traditional theatre, witnessing its ever-evolving forms and resilient vitality of “Pure Cotton and Mixed Fiber.

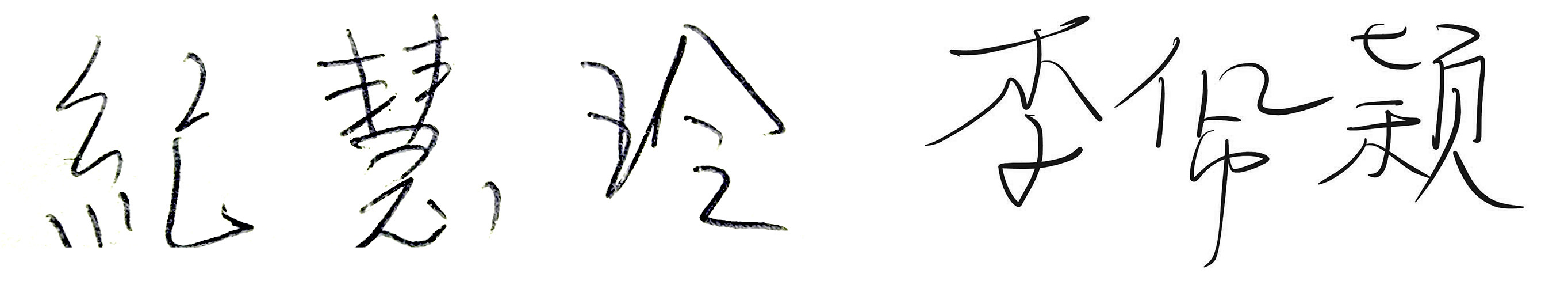

Curator